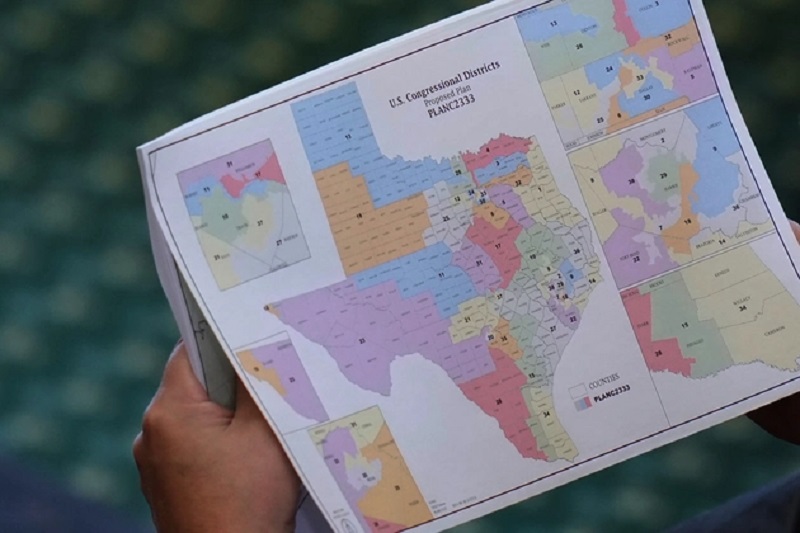

The court's ruling on Texas' new map is headed for the Supreme Court. | Eric Gay/AP

When a judge warns readers to “Fasten your seatbelts!” before a 104-page legal diatribe — best to buckle up.

Jerry Smith, a judge on the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, delivered that admonition before launching into an invective-laden, unusually personal excoriation of a legal decision Tuesday throwing out congressional boundaries Texas just redrew at the urging of President Donald Trump.

Smith, on the losing end of that 2-1 ruling, attacked the plaintiffs as tools of left-wing donors George and Alex Soros, who featured at least 17 times in the ruling. (“George and Alex Soros have their hands all over this.”) Smith swiped at Democratic California Gov. Gavin Newsom (“The main winners from Judge Brown’s opinion are George Soros and Gavin Newsom.”) And Smith went after the plaintiffs’ lawyers and advocates in intensely personal ways.

“That tells you all that you need to know — this is about partisan politics, plain and simple,” Smith wrote.

Although the Trump administration ended the federal government’s role in the litigation earlier this year, Attorney General Pam Bondi endorsed Smith’s dissent Wednesday. “Couldn’t have said it better myself,” Bondi declared in reaction to a social media post highlighting Smith’s remarks about Soros and Newsom.

But Smith, a Reagan appointee, saved his most intense disdain for a fellow jurist, U.S. District Judge Jeffrey Brown, a Galveston-based Trump appointee who authored Tuesday’s ruling scrapping the new Texas map that gave Republicans a five-seat pickup opportunity.

The redistricting ruling is headed for the Supreme Court, which is expected to decide quickly whether to allow it to remain in effect or reinstate Texas’ new, more Republican-friendly map. While the justices often rely on appellate dissents in considering how to deal with cases, Brown’s intense focus on the conduct of his judicial colleague could obscure some of his legal and factual complaints about the ruling, some experts said.

Smith’s umbrage appeared to stem from the speed with which Brown issued the ruling, a move Brown emphasized was intended to allow Texas leaders to return to the state’s earlier congressional boundaries before a Dec. 8 deadline for candidates to declare their bids for Congress.

“This outrage speaks for itself,” Smith wrote. Only it didn’t, because Smith kept going.

While dissenting judges typically refer obliquely to the “majority” opinion, Smith’s relentlessly personal and withering opinion using Brown’s name more than 360 times, often accompanied by colorful insults.

Smith lit into Brown as an “unskilled magician” who “prefers living in fantasyland.” Smith said Brown committed “pernicious judicial misbehavior” by racing to issue his opinion. Smith also slammed Brown as “no stranger to inconsistency,” called him “wrong on multiple levels” and accused him of handing “Soros a victory at the expense of the People of Texas and the Rule of Law.”

“Whether Judge Brown likes it, gravity exists,” Smith wrote.

Although judges typically couch their deliberations in a veil of secrecy, Smith revealed them in great detail, even quoting from the text of email exchanges with Brown as the ruling was being prepared.

Lest anyone be confused, Smith rolled out the phrase, “I dissent” some 16 times.

Smith also concluded his opinion ominously. “Darkness descends on the Rule of Law. A bumpy night, indeed,” he wrote.

Brown did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

The fellow district judge who signed on to Brown’s opinion, El Paso-based Obama appointee David Guaderrama, escaped largely unscathed from Smith’s withering assault. Smith mentions Guaderrama by name only once and alludes to him briefly at one other point.

The rupture between Smith and Brown could be due in part to the fact that the men don’t typically work together. Under a special legal provision passed by Congress, certain redistricting cases go to a three-judge panel instead of a single district court judge. Such panels are comprised of two district judges and one appeals court judge, with appeals of their rulings going directly to the Supreme Court.